It’s time to design your app. Regardless of the platform, you will be faced with a fundamental question that has implications for both users and your business: design native or not.

You can build natively or not, but that’s another discussion. We’re going to talk about native design and user experience.

First, let us define what we mean by a native design. When releasing an app, you’re doing so on someone else’s platform. Be it Windows, Mac OS, the web (less of a “platform” but has similar properties), iOS, or Android – each has its own set of conventions and guidelines for how to create an app that feels more native to the platform. Apple has the HIG for its various platforms, Google created material design for Android and the web has a variety of widely accepted, less formalised conventions on how to design different types of interactions, born from decades of trial and error.

Whatever form these guidelines come in, they are only ever that: guidelines. You are free to design your service however you wish, and many do. But what are the advantages and disadvantages of each approach?

It depends how far your service reaches

If your service is something that only exists in one place (eg: it’s an iOS app), it makes perfect sense to adopt the guidelines of that platform. Your users are used to other conventions in that platforms world, and creating something unique to your brand will only lower the usability. Products that fall into this category are likely to have niche applications or be from indie developers. You will want some brand personality in the design, but the core UX conventions should largely follow that of the platform.

If however, you are on multiple platforms, the decision is more tricky. Larger companies service more customers by ensuring their app is available in as many places as possible. The ultimate manifestation of this is Netflix – one of the reasons they became so widespread so quickly is that they created apps for almost every platform that have a screen and an app infrastructure. But this creates the dilemma of either making your UX consistent across all your apps or choosing to design them native to each platform.

Staying Native

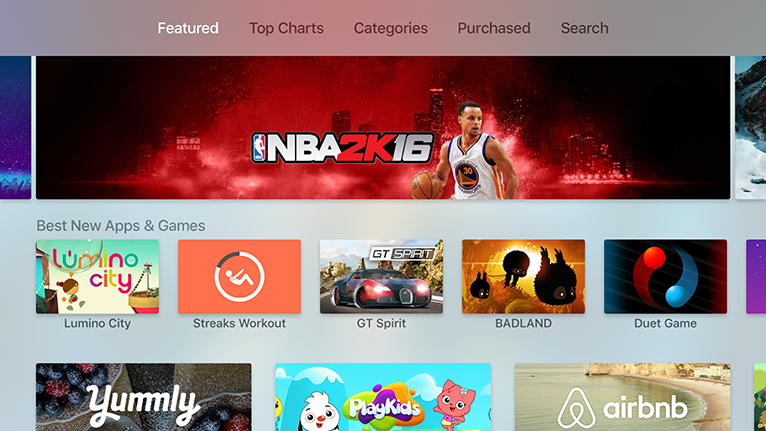

The main benefit to keeping your UX native is that users moving between services on the same platform don’t have to learn anything new. For example, if you release an Apple TV app that has several top-level navigation sections, the established convention is to run these across the top of the window. If you design something non-standard the learning curve increases, reducing the ease at which the users can get to your content, adding friction that affects the experience.

You would hope that the platform owners have tested their approach and guidelines extensively, more than you are likely to for a single service. You should be able to trust that they have made the right design and usability choices, taking away some of the testing burdens if you follow their guidelines.

Designing natively usually means you build natively, which comes with its own benefits of being faster to create. As platforms introduce new features native apps are easier to update and quicker to market than their bespoke counterparts.

Going bespoke

The decision here is very use-case dependent. Users of your service might regularly move between platforms, in which case you might think it makes more sense to have a consistent experience between all of your apps. If you have the type of service where users are likely to actively jump from a browser to a mobile app, or mobile app to TV app, then consistency between those will be important. If your users need to re-learn how to interact with your application on each platform they will become frustrated as users expect the service to behave the same everywhere.

You can, of course, have a service that is in many places, but usage patterns suggest most users only access it on one platform. In these scenarios it might make more sense to lean in the direction of native for the core UX and hierarchy.

There may be financial or business benefits to going bespoke and keeping everything as consistent as possible across platforms, but if you are making product decisions this way you’re doing design wrong.

It is a spectrum

The decision to go native or not with your design isn’t black & white. There’s a whole spectrum to choose from and where it makes sense for you to sit on that spectrum will be different for every business. As with most spectrums, the very extremes are rarely the correct choice for anyone. There may be some core fundamentals of a platform that it makes no sense to change, but you want a particular core interaction or layout to be consistent across your apps.

It goes beyond styling

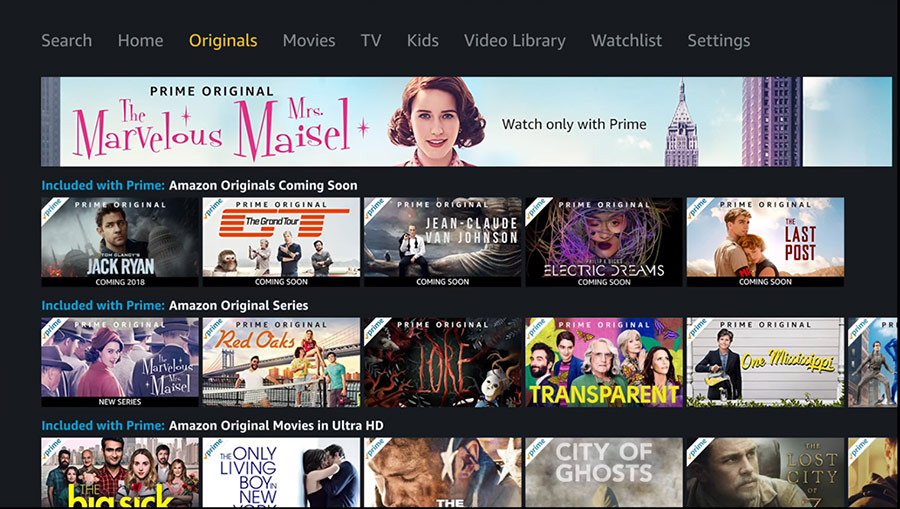

The way things behave is as much of a consideration as how they look. Take the recent launch of Amazon Prime Video on Apple TV. It’s more on the bespoke end of the spectrum. They keep the same basic principle of horizontal lists of landscape cards you navigate between – a commonly accepted standard it seems for TV services – however the size, positioning and behaviour of these varies from the native recommendations.

To pick on one tiny detail in the app: switching primary navigation tabs in Amazon Prime Video. If you’re going to have tabs, make them behave like tabs on the platform. On Apple TV the HIG suggests that simply moving the selection to a tab displays the content for that selection, Amazon requires an additional click to confirm the tab selection. The result of this is that users might be left hanging thinking that the app is just slow to respond, it might take them a while to realise they have to click (if they realise at all).

Apple TV apps generally use sound effects as you move around the UI, including across the primary navigation tabs. The control mechanism of the remote control is remote – the sound is an additional reinforcing mechanism that confirms to users the action they made was registered. Amazon does not use any of these sound effects so users might have to concentrate that much more when using the UI to visually confirm the action they took registered and was as intended.

Going bespoke is fine, but making these kinds of adjustments to well-accepted behaviours on a platform is likely to cause frustration.

Lessons

If you have a mass market who are likely to use more than one platform to access your service, then ensure there is some consistency in the experience – mostly around the overall information architecture and primary navigation paradigm. Make it easy for users to move seamlessly between platforms as much as possible.

It makes sense to take into account platform guidelines or base interaction and behavioural consistency. People get used to using a device and if every service with an app on that device works completely differently, the friction when moving between apps is high. Go with the flow and be a good citizen of the platform where possible.

Avoid completely bespoke implementations that will confuse users and adhere to the base conventions so as not to create unexpected experiences on any given platform. It can be a tricky balance to strike.

When testing your designs it’s important not to test in isolation. Perform tests with users in a way that mirrors active use. Testing anything in isolation is never an accurate reflection of the real world. Your service is not the only reason any user owns a device that runs the platform your service operates within.