The Domain Name System (DNS) is often referred to as the backbone of the internet. It’s run by many engineers and their organizations, it ultimately shapes the future of the internet.

I recently attended ICANN58 in Copenhagen. It was an amazing week of round table discussions about the future of the internet. It included:

- seminars on policy development for the DNS

- workshops on how the architecture for the internet functions

- where the internet’s biggest vulnerabilities lie

It was a lot of fun, and I gained a t0n of value from it.

Just to backtrack a little, I’m relatively new to the domain world and the inner workings of the internet architecture. Since joining this space as a developer with iwantmyname, I’ve had to learn a ton. There’s a massive labyrinth that lies below the browser’s surface. So I wrote this guide to walk you through some of the infrastructure that hides behind those domain names and numbers we all use daily.

How does the internet work?

“This is a very common interview question: what happens when you go to Google.com, enter a query, and press enter?” — Quincy Larson

So you open your browser and go to freecodecamp.com and this awesome site loads up right in front of you in the blink of an eye. You already know that this site is rendered from a range of compiled files that sit on a server somewhere. But how does your browser find its way to those files in the infinitely expanding internet? You may start thinking…

What the heck just happened?

The very first time you went to freecodecamp.com, your browser didn’t know what the IP address for freecodecamp.com was, so it couldn’t connect to and retrieve those files. Nor for that matter did it know where the actual servers were that those files are hosted on. And therefore, it had no idea from where to pull those files to start rendering the page.

So here’s what happens: (cue the graphics!)

OK, let me expand upon that a bit

- A user asks their browser to visit freecodecamp.com

- The browser queries a DNS Resolver (usually their ISP) “where’s freecodecamp.com?”

- DNS Resolver queries the Root servers (which have a big important list that keeps this information) “where is .COM?” Replies with Verisign.

- DNS Resolver then queries Verisign — “where is freecodecamp.com?” Verisign replies with the nameservers ns1.cloudflare.com and the IP address 192.168.178.1

- Hosting servers are queried with the IP address. “Give me the files for IP address 192.168.178.1 (please)”

- Website files are delivered and rendered on the page so user can learn to code…or whatever they were doing.

I grabbed this screencast from Verisign, by far the biggest Registry in the world running .com .net .cc .tv and .name. It shows you the process in a nice way how the protocol works through the sequential queries and responses through the DNS structure.

Don’t worry too much about trying to read all the text, but just watch the exchanges and flow of information to reiterate what we’ve discussed above (it’s on a loop so will restart).

Sourced from Verisign

Who makes it work?

In short IANA, in long ICANN, (I’ll explain these organizations in a moment and all this will make more sense, I promise!)

The reason for explaining how it works, was to uncover who makes it work — the real question and purpose for this article. It’s easy to think things just work. But of course, it’s no accident, the reason the internet works is because of the protocols and policies that have been created and gained enough of a consensus to become universal norms, but who agrees on these and how?

In short, and with specific regard to how domain names and IP addresses are mapped, that function falls under the competency of IANA (Internet Assigned Numbers Authority). They have the mandate of making sure the correct technical procedures are in place to have a safe and stable Domain Name System. Which brings us to ICANN (Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers). There’s no discussing IANA without ICANN:

Besides providing technical operations of vital DNS resources, ICANN also defines policies for how the “names and numbers” of the Internet should run. The work moves forward in a style we describe as the “bottom-up, consensus-driven, multi-stakeholder model” — ICANN.COM

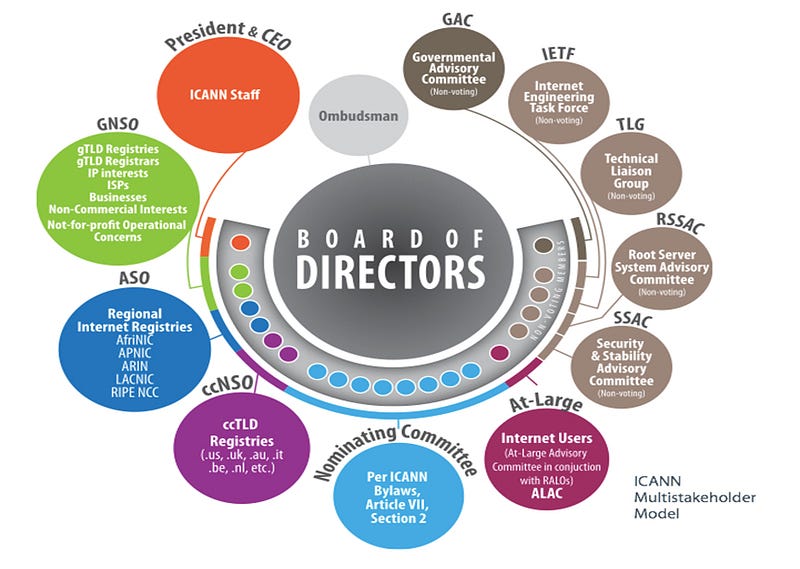

In September of 2015 the IANA function which has been run by ICANN since 1998 permanently transitioned from being under a contract with the United States Department of Commerce to the autonomous control of ICANN \o/ ICANN has a board of directors and as a body, is divided up into separate member groups, let’s explore the Multi-stakeholder model:

“ICANN’s inclusive approach treats the public sector, the private sector, and technical experts as peers. In the ICANN community, you’ll find registries, registrars, Internet Service Providers (ISPs), intellectual property advocates, commercial and business interests, non-commercial and non-profit interests, representation from more than 100 governments, and a global array of individual Internet users. All points of view receive consideration on their own merits. ICANN’s fundamental belief is that all users of the Internet deserve a say in how it is run.” — ICANN.COM

While it is fair to say all these groups are “represented,” I would argue all are are not represented equally. It’s natural to expect that those with more financial stake and cash to burn will try to pull the conversation in a certain direction. For example, telecoms like AT&T, Comcast, Charter, Verizon, Vodafone, T-Mobile, Orange.

They will arguably pull us in a backward direction, where they can package up websites like they did with cable TV channels, and sell them to end users, toll the traffic on the cables they control, and generally triple-dip on a more closed internet so they can make even more profit.

Some Governments will also try to influence in a direction toward their own state-interest, while others will try to be more global citizens. Intellectual Property advocates (organizations that are usually made up of IP lawyers) want things to be more about IP and brand security, so they can protect the lucrative rights of their high paying clients.

Service providers in the commercial sector like Google and Facebook are visible in the array, and tend to advocate — in part at least — for their users’ privacy, along with maintaining their own domination of the web.

Registries like Verisign, have an interest in designing favorable policy outcomes to which they are bound to comply.

Interestingly in my experience it is the Registrars — where you can register domain names (like iwantmyname) — who provide a voice of reason in the fray. They have to balance their obligations to ICANN and the Registries against those of their customers. And as a result of this, they often have to push back against various members or interest groups, or at times even the ICANN board itself.

Let’s talk end users

Hey! That’s us!

There’s a significant lack of end-user engagement in this process. Well, we’d all be better off if the end users of the internet started paying more attention.

Remember that there are some 3.7 billion internet users, but there are only a few people who own stakes in telecoms, registers, or web platforms. The freeCodeCamp community alone has more than a million users, and together we share so much that’s at stake.

This said, the number of folks currently engaged in this discussion is very small — maybe only a few thousand people. To be honest, I think there’s a growing need for more of us developers to take a more active voice in the conversation.

This is, after all, our livelihood. It’s where we tend to spend our time. It’s the space that consumes much of our focus, energy, and passion. And apart from being highly savvy and heavy users of the internet, we also have unique insights into our own audiences. We can speak with an empathetic voice that resonates with an even larger end user base.